TERENTIUS.

De zes comedien van P. Terentius. Verduitst door Henricus Zwaardekroon, rector der Schole, tot Rotterdam.

Rotterdam, Gedrukt bij Johannes Naeranus, 1668.

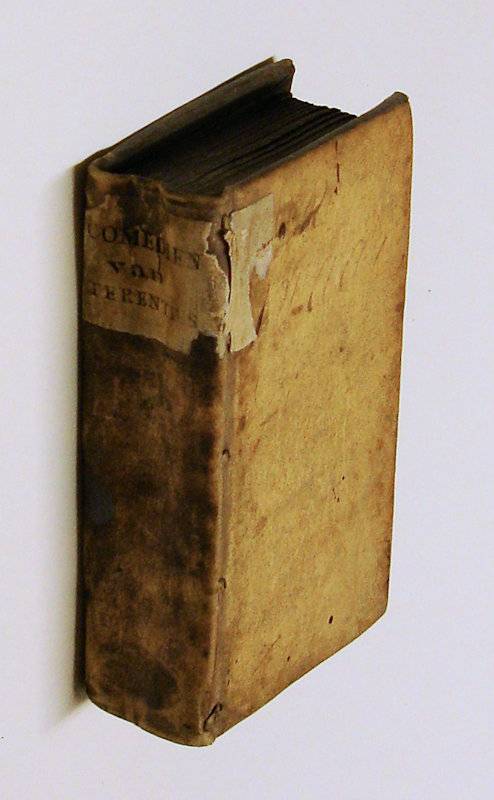

12mo. 498,(6 blank) p. Vellum 12.5 cm (

Ref: Geerebaert 138,11,6; OiN 362) (

Condition: Binding scuffed, spotted and soiled. Frontispiece removed. Oval stamp on the title. Some worming in the blank upper margin, occasionally nibbling at letters. Paper yellowing) (

Note: The late antique grammarian Aelius Donatus (4th century A.D) wrote not only a commentary on the plays of the Roman playwright Publius Terentius Afer, ca. 190-159 B.C., but also a short biography, in which he tells that Terentius was born in the Roman province Africa and that he came as a slave in the houshold of the senator Terentius Lucanus. He adopted his name when he was manumitted. Terentius is the author of 'fabulae palliatae', which means 'plays in Greek cloths'. He adapted Greek plays, especially those of the Greek playwright Menander, to the taste of the Romans. Six of his comedies have survived. For later generations he became a model for elegant Latin. His style was closer to everyday conversation than Plautus', an earlier contemporary comic playwright, whose style was more extravagant. He was quoted by Cicero, Horace, Persius and the Church Fathers. Ever since antiquity he lived also a long and influential life in schools as a model for Latin language and rhetoric. In the Middle Ages he was read for his moral sentences. He was imitated by the German abbess Hrotsvitha of Gandersheim (ca. 935 - ca. 973) in her 'Dramenbuch', with which she wanted to create a Christian alternative for the pagan comedies. With the coming of humanism Terentius enjoyed a renaissance in the classroom and on stage. Scholars rejected the 'barbaries' of Medieval Latin and chose the elegance of Cicero and Terentius as their model. In his 'De ratione studii' (1511) the Dutch humanist Desiderius Erasmus, 1466-1536, encouraged the study of Terentius for his language and moral utility. 'Among Latin writers, who is more valuable as a standard of language than Terence? He is pure, concise, and closer to everyday speech and, by the very nature of his subject matter, is also congenial to youth'. (The Classical Tradition, 2010, p. 930) Erasmus published later in life, in 1532, an edition of Terentius' plays. Erasmus seems to have learned the whole of Terentius by heart in his youth. He admired the author for his 'latinitas' and his civilized humor. His ideal as a humanist and pedagogue was the creation of better men with the help of the classics. He held the opinion, that schoolboys should read Terentius over and over again. Thus they could master a pure Latin style, and learn at the same time good morals. Several Dutch humanists wrote 'Dialogi pueriles', fictitious dialogues to train schoolboys to converse in Latin; conversations which much Terentius in it.

§ The first Dutch translation of Terentius appeared in 1555 in Antwerp. Almost one century later 2 other new translation followed. In 1646 the remonstrant reverent Henricus Oosterhaern published a prose translation in Rotterdam. His translation is as literal as possible. His aim in didactic. He hopes that his readers will polish their speech and style when reading Terentius, that they will learn from Terentius a 'suyvere en cierlijke manier van spreken en schryven'. (P.J.M. van Alphen, Nederlandse Terentius-vertalingen in de 16e en 17e eeuw, Tilburg 1954, p. 95) Two years later, in 1648, Rotterdam saw the next and more elegant prose translation, now by another remonstrant, the schoolmaster Henricus Zwaerdecroon, since 1634 Rector of the 'Schola Latina Erasmiana'. (NNBW 5.1182/83) In the dedication in this edition to his 'alumnus' Adrianus de Matenesse, Zwaerdecroon dwells on the diligence and enthousiasm he and other old schoolboys displayed while reading Terentius. On their request, Zwaerdecroon tells us, and because they are leaving for the university he made this translation. Sometimes we find in the Dutch translation words or passages printed in italics. Those words and passages have been added to improve the Dutch, and to explain matters. The edifying comedies of Terence were not only read by schoolboys. The Dutch philosopher Spinoza must also have studied his Terentius very thoroughly. In his work hundreds of quotations and borrowings from Terence can be traced. Spinoza used them to define and illustrate human feelings, weaknesses and passions. (F. Akkerman, Spinoza's tekort aan woorden, Leiden, 1977, p. 3) In the same year as this edition (1648) the Rotterdam printer Naeranus brought a translation only edition on the market. This translation was reissued again in 1668, this edition) (

Provenance: Stamp on the title: 'Bibliotheek Missiehuis Tilburg) (

Collation: A-X12 (leaves X10, X11 & X12 blank. leaf A2, the frontispiece, gone) (Photographs on request)

Book number: 120174 Euro 200.00

Keywords: (Oude Druk), (Rare Books), Komödie, Latin literature, Terence, Terentius, Terenz, comedy, römische Literatur

TERENTIUS.

TERENTIUS.