JUVENALIS & PERSIUS. D. Junii Juvenalis et Auli Persii Flacci Satyrae: cum Veteris Scholiastae & Variorum Commentariis. Accurante Cornelio Schrevelio.

Leiden (Lugd. Batav.), Ex officina Hackiana, 1671.

8vo. (XVI),604,(42 index) p. Vellum 20 cm (

Ref: STCN ppn 840013876; Schweiger 2,511; Dibdin 2,154; Moss 2,158/9; Ebert 11242; Graesse 3,520) (

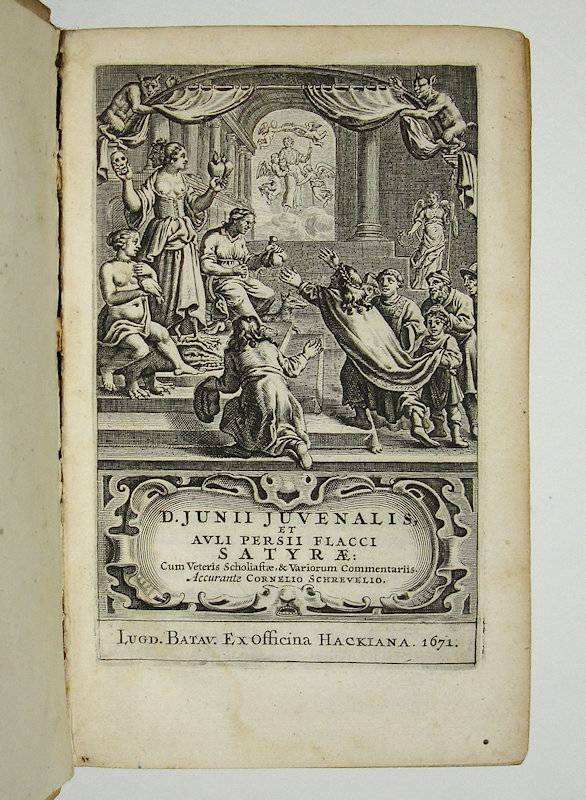

Details: 5 thongs laced through both joints. Short title in ink on the back. The engraved title, which is not signed, is used here for the third time. It was first used for the original edition of 1648, for a repetition in 1658, and for this 1671 reissue. In 1648 the engraved title still bears the name of the engraver, it is executed by the Dutch Golden Age engraver Reinier van Persijn. The title depicts a complicated allegorical scene: on the left a naked woman sitting on a crocodile, holding in her hand a parrot; then a Janus-headed woman, with bird feet and a tail, holding up in her left hand a Momus-mask, and in her right 2 flaming hearts; in the centre sits on a throne an old woman, holding in her left hand a sack of money (?), and in her right what seems a little flask; on the right in the foreground a king reaching for that sack; he is accompanied by a priest, a farmer (?) and a soldier; in a window central above the old woman we see the ascension of the poet. See for an explanation of the allegory the note below) (

Condition: Vellum age-toned and soiled. Boards worn at the extremities. Front hinge cracking but still strong. Front flyleaf loosening. Name on the front flyleaf. Small old inscription on the rear pastedown. Occasional small ink underlinings. Small wormhole in the right lower corner of the first 14 gatherings, never even coming near to the text) (

Note: The Roman poet Juvenalis, ca. 55-140 AD, was the last and most influential of the Roman satirists. He 'uses names and examples from the After p. 65 has been added a plate showing a allegoric triumph scene with prince Frederik Hendrik of Orange. See for this plate: rkd.nl/nl/explore/portraits/record?filters[plaats][]=Den+Haag&filters[kunstenaar][] =Vinckboons%2C+David+%28I%29&query=&start=2)past as protective covers for his exposés of contemporary vice and folly'. His main theme is the dissolution of the social fabric. (The Classical Tradition, Cambr. Mass., 2010, p. 501) The satires of the stoic poet Aulus Persius Flaccus form one 'libellus' of 6 satires, together 650 hexameters. 'They are well described as Horatian diatribes transformed by Stoic rhetoric'. 'He wrote in a bizarre mixture of cryptic allusions, brash colloquialisms, and forced imagery'. (OCD, 2nd ed. p. 805) This edition of 1671 is a 'Variorum' edition. It offers the 'textus receptus' which is widely accepted, accompanied with the commentary and the annotations of specialists, taken from earlier useful, normative or renewing editions. Editions like these, 'cum notis Variorum', were useful, but never broke new ground. The production of this kind of editions was the specialty of Dutch scholars of the 17th and 18th century. The compilers seldom were great scholars, but often hard working schoolmasters. Their involvement in publishing a new edition was limited to the necessary, but ungrateful task of the beast of burden. Such a plodder was the Dutch editor Cornelius Schrevelius, who taught classics at the Schola Latina at Leiden, where he had been raised himself. In 1642 he succeeded his father, Theodorus Schrevelius, as the rector (Moderator) of the school. He raised at least 11 kids, and fell in 1664 victim to the then raging plague. His first Juvenal edition he published in 1648, and it was reissued by Hackius in 1658, 1664 and in 1671. Schrevelius' aim was to promote the studies of his young students and to instill in them a necessary fear (optatam metam), which would make them useful citizens and the pride of their parents. Juvenal is a suitable author for such an enterprise, for he flogs wrongdoers, and learns them to avoid the path of wickedness and to embrace honesty. (Dedicatio p. *2 verso) Especially in shameless times as ours, he continues, satyre is needed. Decent behaviour and faith have been replaced by deceit and swindle. In a short 'Benigno Lectori' (*4 verso and *5 recto) Schrevelius tells that he relies for the text on the earlier editions of Robertus Stephanus and Pithoeus, and that he excerpted the notes and commentaries of Lubinus, Farnabius and Casaubon. In addition he offers, he says, a complete and emendated edition of the old Scholiast. Schrevelius even used two excellent manuscripts which were lent to him by the Leiden professor Salmasius, which, he tells, helped him to solve many difficult problems.

§ The engraved title deserves some attention. The easiest description we found was 'an engraved title with many figures'. To us, it seems an allegorical scene based on the tenth satire, Juvenal's famous declamation on the folly of men in desiring in their prayers from the gods vane things as honor, fame, wealth, power, beauty, or a long life, instead of a sane spirit in a healthy body. 'Whole households have been destroyed by the compliant gods in answer to the masters' prayers. In camp (nocitura militia) and city (nocitura toga) alike we ask for things that will be our ruin'. (Vss. 7/9, in the Loeb-translation of Ramsay) Juvenal offers a list of pityful examples, such as the once powerful Sejanus, who like the Libyan general Gadaffi many centuries later was 'being dragged along by a hook, as a show and joy to all'. (Vss. 66/67, translation Ramsay) Victims of their lust for power were Alexander the Great, Xerxes, or the punic conqueror Hannibal, the man who was once about to destroy Rome. We assume that the royal figure who reaches out for the sack of money, or from whose hands it is being snatched, is Hannibal. The clue for this assumption is the woman on the crocodile. Such a woman was in 17th century iconography the common personification of Africa, for instance on maps. The fate of this scourge of Rome is treated by Juvenal in evocative language in 20 beautiful verses. It begins like this: 'Put Hannibal into the scales; how many pounds' weight will you find in that greatest of commanders? This is the man for whom Africa was all too small'. (vs. 147/8). Together with the old woman he is the central figure on the title. The positioning of the three woman brings in mind a Triad, a triple diety, such as the Graces, the Moirai or Fates, or the Harpies. The Erinyes, the avenging spirits, also sometimes form a trinity. The standing woman seems to be a mixture of an Erinye and a Harpy. She has some features of such a Harpy, the personification of deamonic powers, and an agent of terrible punishment. She is bare breasted and stands on huge bird claws, with which she abducts the souls of the dead to their doom. In her right hands she holds, instead of the usual horrifying snake, a Momus mask, which personifies satire and mockery, the power to make a fool or ass of someone. In her left hand rest two flaming hearts, catholic imagery, distastful to the protestants, and therefore perhaps reprensenting idolatry. Her double faced Janushead, looking to the future and the past, might be an image of Time. The old woman on the throne is the central figure on the title. To her all movement on the picture is directed. She has the features of Atropos, the riged and inflexible one, the oldest of the 3 Moirai, or Fates, and in iconography often depicted as an old woman. She has power over life and death, and represents the fate that cannot be avoided. She holds Hannibal's fate in her hands. She withdraws the sack of money (power) and offers with her right hand the once mighty suppliant a little flask or small beaker, with the invitation to poison himself. Juvenal on Hannibal's unglamorous bleak death: 'What then was his end? Alas for glory! A conquered man, he flees headlong into exile, and there he sits, a mighty and marvelous suppliant, in the Kings's antichamber, until it pleases his Bithynian Majesty to awake! No sword, no stone, no javelin shall end the life which once wrought havoc throughout the world: no, but that which shall avenge Cannae and all those seas of blood, a ring (containing poison)'. (Vss 158/165, translation Ramsay) The engraver follows for this scene the better known version of the Roman historian Livy. In chapter 51 of the 39th book of his History of Rome, 'Ab Urbe Condita', Livy tells that Hannibal took his poison in an 'poculum' cup/goblet/bowl/beaker) (

Provenance: Manuscript ownership entry of 'A.J. Enschedé' on the front flyleaf. Adriaan Justus Enschedé, 1829-1896, was a member of a famous Dutch dynasty of printers. His forefather Izaak Enschedé established himself in Haarlem in 1703, and there the firm remained for more than 300 years. The firm was, and still is famous for the quality of its printing of bonds and banknotes. In 1810 they printed the first Dutch banknotes. Adriaan Justus entered the firm and kept it flourishing. From 1857 onward he was also Keeper of the archives of the city of Haarlem. He wrote several books on the history of Haarlem, and on the history of the Wallon Church in the Netherlands) (

Collation: *8, A-2R8 2S4 (2S4 blank)) (Photographs on request)

Book number: 130097 Euro 170.00

Keywords: (Oude Druk), (Rare Books), Altertumswissenschaft, Altphilologie, Antike, Antiquity, Hannibal, Iuvenalis, Juvenal, Juvenalis, Latin literature, Satiren, Satires, Satyrae, Schrevelius, classical philology, römische Literatur

JUVENALIS & PERSIUS.

JUVENALIS & PERSIUS.