LIBRI DE RE RUSTICA.

Libri De Re Rustica a Nicolao Angelio viro consumatissimo nuper maxima diligentia recogniti & typis excusi, cum indice & expositione omnium dictionum. Catonis, Varronis, Columellae, Palladii quae aliqua enucleatione indigebant. Additis nuper commentariis Iunii Pompo. Fortunati in librum De cultu hortorum, cum adnotationibus Philippi Beroaldi.

N.pl.(Florence), n.d. (Colophon at the end: 'Florentiae per heredes Philippi Iuntae, Anno Domini 1521, Die XXVIII. Mensis Septembris'), 1521.

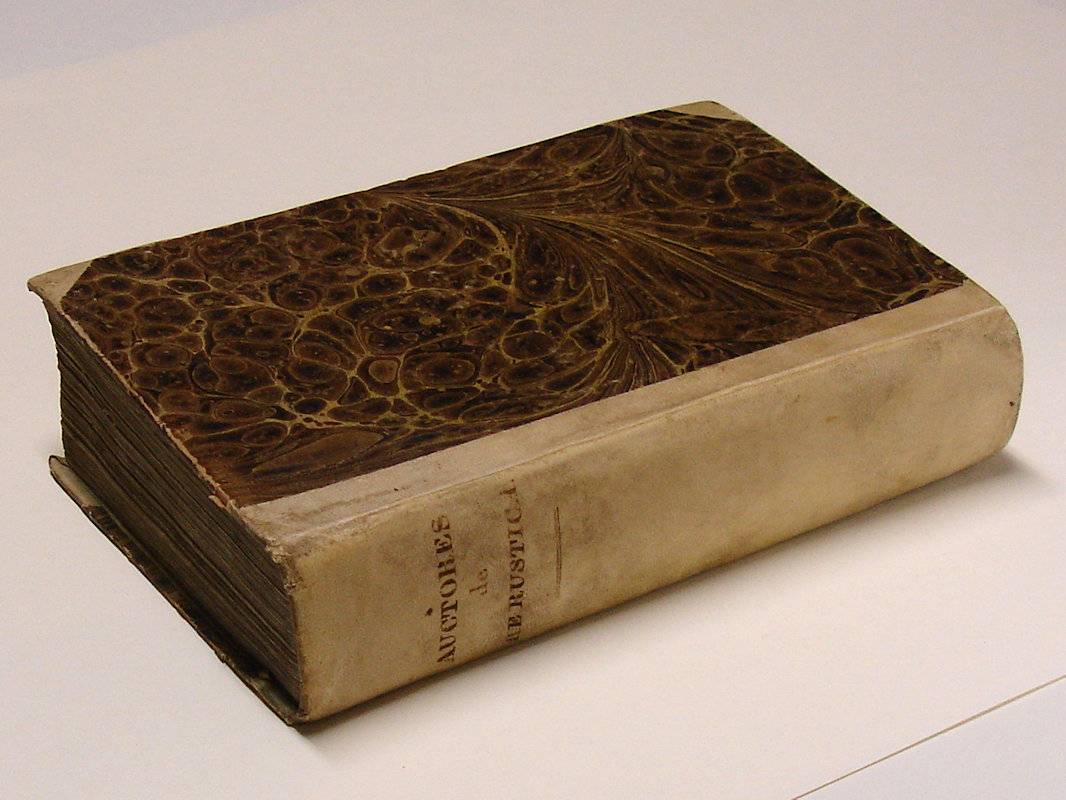

4to in 8s. 2 parts in 1 volume: (XX),218 (recte 222);125 leaves. 19th century half vellum 22 cm. (

Ref: Edit 16 28760; Schweiger 2,1305/06; Renouard, 'Annales des Imprimeries des Alde', 'Notice sur la famille des Iunte', p. XLVI; Adams S807; Ebert 20736; Brunet 5,246; Graesse 6/1,331) (

Details: 19th century binding, with short title on the back and marbled boards. Good quality white paper. Some text diagrams. Iunta's printer's device on the verso of the last leaf) (

Condition: Some wear to the extremities. Small wormhole in the right upper corner of the first leaf. Old ownership entry below the printer's device. Small booklabel on front pastedown. A small pinpoint wormhole in the upper margin of the last 8 leaves, pinpoint wormhole in the inner margins of the gatherings l and m. Some old ink underlinings, 2 old ink annotations. Small rust hole in the upper corner of leaf 175. Some slight foxing and soiling of the paper. Small stain in the upper margins of 2 gatherings. The gatherings collate correctly. The page numbering of the second part has some irregularities, but is alltogether correct) (

Note: This Italian edition of the Libri de Re Rustica, first published by Philip Junta in Florence in 1515, gives us the works of four Roman gentlemen-farmers and landowners, Cato, Varro, Columella and Palladius, who wrote about agriculture and were also successful practical farmers. As a cultural movement the Italian Renaissance was the product of the aristocracy and the ruling elite. The greater part of the populace were still rural peasants. Most of them worked on private farms or were tenants who shared the crops with their landowners. The urban elite of this time turned themselves into landed aristocracy, owning large villa-farms. Capital produced by commercial and trading activities was invested in land. 'It was particularly in the Florence area that this bourgeois colonization of the surrounding countryside coincided with the development of a trading economy'. (G. Gobbi Sicap, 'The Florentine Villa: Architecture History Society', Abingdon, New York 2007, p. 11) Land, and a house in the country lent prestige. 'A landlord of this period who had entrusted his property to a share-cropper frequently visited his lands and oversaw every activity that took place, keeping an eye on the stables and cellars and taking charge of the sale of the produce; he thus appeared to participate fully in farming life' (Idem, p. 14) Thus the residential extra-urban villas of the 'signori' became 'of central importance to the development of the newly-dawning Renaissance culture' (Idem, p. 15) The rediscovery of classical authors in the early days of humanism provided important confirmation of these aspirations. 'The 'Rei rusticae scriptores' who now took the stage - including the Romans, Cato, Varro, Columella, the 'rusticus' Palladio, (... ) provided further food for thought, adding value to the literary notion of a house in the country as a refuge, corresponding to the classical 'topos' of the joys of country life, and the practical and educational concept of farming as the purpose and 'magistra of life'. The ideology of the paired words 'utilitas-delectatio', a humanist concept, dates back to classical times and appears in the works of the most authoritative Latin writers, including Cicero, Seneca and Pliny'. (Idem, p. 19)

§ The aim of Cato, Varro and Columella was to bring Roman farming of their time on a higher level. The conjunction of these three didactic texts can be found from the Middle Ages. They were jointly published for the first time in 1472 in Venice, and form the chief texts on agriculture and rural life in antiquity. The oldest of the trio is the Roman politician Marcus Porcius Cato, 234-149 B.C., the source of famous maxims for orators, like

'rem tene, verba sequentur'.

In style and in character he was a typical farmer, shrewd, hardworking, frugal, honest, sincere, but limited. His 'De re rustica', also known as 'De agri cultura' is a kind of commonplace book. It gives us a view of the life of an oldfashioned landowner in that age, and offers information on Roman cult and rustic folklore. The second work was written by possibly the greatest scholar Rome produced, Marcus Terentius Varro, 116-27 B.C. Of the mass of works he wrote only one is preserved to us completely, 'De re rustica'. He was a landowner on a large scale, who wrote the book in his eightieth year (annus octogesimus), he tells us in the beginning, 'ut sarcinas colligam ante quam profiscar e vita'. It is a philosophic dialogue in 3 books, in which he gives sound and practical advice for managing a farm (I), a stock-ranch (II), poultry, aviary and herb-garden (III). 'While giving interesting information on the state of agriculture at that time, it is withal a pleasantly discursive book, the work of a garrulously entertaining old scholar' (H.J. Rose, 'A Handbook of Latin Literature', London 1967, p. 222). Lucius Junius Moderatus Columella was a contemporary of Seneca. He wrote his 'De re rustica', consisting of 12 books, ca. 60-65 A.D. He was a practical farmer on a large scale, who was concerned over the decline of the agriculture in his days. 'Book 1 deals with general matters of buildings and labour, 2 with soils and crops, 3-5 with vines, olives and fruittrees, 6-7 with domestic animals, 8 with poultry and fishponds, 9 with game and bees, 10 (in verse) with gardening, 11 with the bailiff's duties and the farmer's calendar, 12 with the bailiff's wife's duties'. (OCD 2nd ed. p. 268) A separate book on arboriculture, part of a larger work, survives too. His style is straitforward and pleasant. The late antique Roman author Palladius (ca. 400), who also seems to have been a landowner, produced a kind of abridgment of Columella.

§ The texts of these four were edited, we are told in the preface, by the Florentine classical scholar Nicolaus Angelius Buccinensis (Niccolò degli Angeli, or Angelio Bucinense, or Bucinensis) who produced many editions for Giunta, e.g. of Plautus, Terentius and Nemensianus. Nicolò degli Angeli was professor of Latin & Greek in Florence. ('vir de utraque lingua benemeritus' (p. AA1 verso)) He was born in Bucine in 1448 and died ca. 1529) (

Provenance: The provenance of this book is dealt with in a longer article than usual, because it sheds some interesting light on the English booktrade in the first half of the 20th century, and on the history of a Russian refugee family. The search for information about previous owners often brings the antiquarian bookseller to unexpected places, in this case to a beautiful portrait of a young woman, a masterpiece of the Russian painter Kardovsky. And it sometimes occurs that the offspring of a former owner kindly offers to provide supplementary information.

§ On the front pastedown of this book has been pasted a booklabel in Russian and in English: 'ex libris Boris Alexandrovitch Chroustchoff'. In the 'Guggenheim Museum collection: paintings, 1880-1945' we found at first the following concerning the provenance of a painting of the mother of Boris Alexandrovitich Chroustchoff, Marya Anastasievna Chroustchova, made by the Russian painter Dimitry Kardovsky (1900): 'Biographical information (...) is fragmentary. According to their son, the late Boris Chroustchoff, who was in correspondence with J. J. Sweeney in 1959-60, his parents owned a large estate in southern Russia as well as a house in Munich and one in St. Prex near Geneva. (...) Boris Chroustchoff adds that his father was 'a very great friend of Kandinsky and other members of the Blaue Reiter school (especially Javlensky). Both Kandinsky and Javlensky often used to stay with us in the Ukraine, and were constant visitors when we lived in Munich. Our house was always full of painters, who found a very good subject in my mother. In fact Javlensky painted a very fine portrait of her in a red dress which has now disappeared' (letters of December 27, 1959, and January 10, 1960). (The attribution to Javlensky is incorrect. It was Kardovsky) Marya Anastasievna and Alexander were separated in 1901. She returned to Russia with her daughter, who died soon afterwards, and Marya herself apparently perished during the Revolution. Alexander remained in Western Europe with his son Boris and they moved to England. (...) Boris' 'father Alexander took the portrait with him to England, where it hung in their house in Harrow-on-the-Hill until 1908, when it apparently disappeared (correspondence with the Museum, 1960). Whether it was actually stolen, or whether it was sold remains to be established. Boris Chroustchoff has since died, and further information has not hitherto been discovered'.

§ In January 2020 we received in an email supplementary information about the owner of this book and about the painting of Kardovsky, from the daughter of Boris Chroustchoff, Natasha de Chroustchoff, offspring from his second marriage, who is living in Great Britain. She wrote us that Boris Chroustchoff (1892-1968), 'was a very interesting but elusive man whose name can be found mentioned en passant in the lives of others with stronger claims to fame'. His father Alexander sent him to an English public school (Harrow) in 1906. He also bought a house in the vicinity of the school where the portrait of Marya Anastasievna Chroustchova hung on the stairs. After he left school in 1909 he lost sight of the painting of his mother. His daughter, Natascha de Chroustoff, writes that possibly Boris' stepmother was not prepared to give it room in their house.

§ After his studies Boris learned the trade from the wellknown London bookseller Irving Davis and the Italian bookseller Guiseppe (Pino) Orioli, who set up a bookshop, 'Davis & Orioli' in Museum Street in 1913. Davis died in 1967. Orioli had learned in his turn the trade from the notorious antiquarian bookseller Voynich (of the famous Voynich Manuscript). 'In the early 1920s Boris with his friend and business partner Lionel Jellinek opened the Salamander Bookshop in Silverstreet (now Barter Street) in Bloomsbury, London', Natasha informs us. The shop was named after the Croustchoff family crest. Young Boris was the bibliographic expert. 'He specialised in medicine, natural history, cookery and Russica with a particular interest in incunabulae'. I, writes Natasha, 'believe they did pretty well until the Wall Street crash of 1929'. 'There are stories about the rather eccentric manner in which my father conducted his affairs: snatching a book out of a potential customer's hand because he didn't like the look of him and so on'. Boris compiled for his own bookshop 5 catalogues which were considered exemplary.

§ The painting of his mother popped up in the Guggenheim Museum, that acquired it from the German art dealer Otto Stangl in 1950. In 1999 Nathasha was allowed to see the painting in the Guggenheim Museum, where it was held in depot. In May 2015 Sotheby's in New York auctioned this painting. It was sold, with the incomprehensible wisdom of the Museum, to benefit the Museums' acquisition fund. Its location now cannot be traced. (sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/lot.86.html/2015/impressionist-modern-art-n09354) (See for this portrait also Wikipedia's article on Kardovsky)

§ Under printer's device in old ink: 'A Fabii Astinea'.

§ On the pastedown also the name of the next owner 'V.E. Watts'. One V.E. Watts produced a Penguin translation of Boethius, 'The Consolation of Philosophy') (

Collation: AA-8, BB-12; a - z-8, &-8, ?-8, R-8; Aa-8, Bb-6, A-10, B - O-8, P-12; pagination: (20),218; 1-20, 235-238 (4 leaves), 24-34, 249-254 & 215-216 (2 leaves), 43-76, 291-294 (4 leaves), 81-125) (For 4to in 8s, see Gaskell p. 106)) (Photographs on request)

Book number: 130102 Euro 1100.00

Keywords: (Oude Druk), (Rare Books), Cato, Columella, De re rustica, Florence, Landwirtschaft, Latin literature, Palladius, Renaissance, Varro, agriculture, antike altertum antiquity, römische Literatur

LIBRI DE RE RUSTICA.

LIBRI DE RE RUSTICA.